Film and game production use similar tools, but for a long time, the two followed parallel but divergent development paths. Films relied on render farms for their beautiful prerendered imagery. Games had to operate in real time and thus relied on game engines for the output, always straddling the line when it came to image quality and performance. Over the years, those two paths came closer and closer. Now, game engines are becoming a key tool in the filmmaker’s toolbox, especially as virtual production increases, and one filmmaker that is taking the use of game engines—Epic’s Unreal Engine, in particular—to new extremes is Hasraf “HaZ” Dulull of Haz Film.

For years, people have talked about the convergence of films and games, and how the chasm between them has been getting smaller and smaller. It has long been the topic of articles in trade publications (I had written a number of them myself) and conference panels at industry trade shows such as Siggraph. For years now, many of the same content creation tools were being used across gaming and film, but the processes and requirements—particularly in terms of rendering (offline vs. real time)—were worlds apart. However, times have changed.

Today, game engines have become the bridge that unites these once similar but very disparate worlds. And companies like Epic Games and Unity have proven their engines’ mettle within the film world with in-house-produced movies such as “A Boy and His Kite” and “Adam,” respectively. These engines have also found their way into the hands of external filmmakers, including Hasraf “HaZ” Dulull.

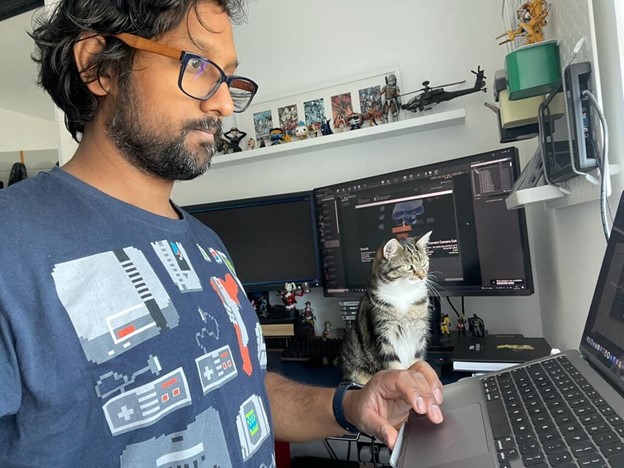

Dulull describes himself as a multidisciplinary filmmaker on at least two fronts: one, filling various roles such as writer, producer, director, and animator, and two, using a tool that’s vital to game development, a game engine, for film production.

Dulull started his career in full-motion video (FMV), creating video game cinematics back in 1997–1998, when the image fidelity wasn’t anywhere near what it is today. He then switched genres, becoming a compositor, previs artist, and, later, a VFX artist and VFX supervisor, working on films such as 10,000 BC, Prince of Persia, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Dark Knight, and Sweeney Todd.

Eventually, Dulull began making short science-fiction live-action/VFX films such as “I.R.I.S.,” “Sync,” and “Project Kronos,” which he made entirely with Adobe Creative Cloud applications at a cost of approximately $3,730. His filmmaking career took off, leading to a deal to write, direct, and co-produce his first feature film, The Beyond, which was released in late 2017 and based on his short film “Project Kronos.” In 2018, he directed and co-produced his second film, 2036: Origin Unknown, based on a short story he had written.

In 2019 or thereabout, Dulull began exploring the use of Unreal Engine to block out shots on the computer as an alternative to using expensive software like Autodesk’s Maya or Maxon’s Cinema 4, or even hiring a previs company like The Third Floor.

“I was just blown away,” Dulull says of using Unreal Engine, adding that when working on The Dark Knight, the group was working with really rough shot blocks, like T-pose characters sliding across the floor, just to get an idea of the composition. Conversely, with UE 4.14 and 4.15, he was getting shadows, reflections… “all this stuff for free and in real time—I wasn’t rendering. I was using Unreal on my MacBook Pro.”

A year later, Dulull began using Unreal Engine for pitch videos, providing executives a detailed look at his film project. “They were totally able to get it, and it would be a quick yes or no, as opposed to them being unsure as to what I was trying to convey,” he says. Some people asked him if the pitch was for an animated film, commenting that it looked like a first-pass animation. The seed was planted, and soon he began using Unreal Engine for some shots for the CG short “Battlefield.”

During the pandemic, adult animation was rising in popularity. And Haz Film (and then Hazimation, a division of Haz Film) was formed, having received a boost from the Epic Mega Grant Program. By using the game engine as the foundation for their work, Haz and his small team have been able to expand their filmmaking (feature films) business model to include a free video game using the IP from the feature films. The live-action features 2036: Origin Unknown and The Beyond were released on streaming services; meanwhile, Haz has five other projects in various stages of development/production. It’s difficult to keep up with him. Besides his own work, he has directed episodes of the Disney action-comedy miniseries Fast Layne, after impressing Disney Channel executives with his vision for the eight-part series. He also directed the animated short bridge film “Descendants—Under the Sea” for Disney and a segment of the sci-fi horror anthology Portals from Screen Media.

A change of pace

Game engines have become an important tool in creating digital content of all kinds. With Unreal Engine, for instance, Dulull can work at a much faster pace and produce stunning graphics, all while employing a very small team comprising an average of a dozen creatives. Also, he maintains the learning curve for the engine is short—he learned it over a weekend, thanks to the community and available resources behind it; in comparison, it took him months to learn Maya.

While Dulull gravitated toward Unreal Engine a few years ago, he notes that UE and Unity both provide similar real-time results; he believes the difference between them comes down to the people using them. Dulull comes from an artist-heavy background, so it’s very much about the cinematic results. Unity, on the other hand, is more program-driven, he feels, and requires more processes to get those results, “and that does not really work with the way I work.”

Game engines change the filmmaking process from a very linear workflow to one that is iterative and agile. As a result, Dulull can produce numerous versions of something that he can present quickly. For instance, when a character is fully finished, a right click will replace that character with the latest version (as long as it retains the same skeleton). Changes requested by producers were easy and inexpensive to make, although this can be a double-edged sword because filmmakers may find themselves consumed with tweaks and changes.

“Imagine doing a screen test—you have to screen-test your movies—and the audience doesn’t like a character’s outfit or hair color. To go back and make those changes is a producer’s nightmare using traditional workflow. Because we’re working in real time, we just have to re-export those frames—that’s OK, we’re not compositing. It’s a big advantage,” he says.

While Unreal Engine offers many advantages, the characters themselves at Haz Film are still created in traditional DCC software such as Blender, Maxon’s Cinema 4D, or Maya, and then are exported in an Alembic or FBX file format to Unreal Engine, where shaders and so forth are updated. “This means we can use whatever tool we want and not have to worry about the pipeline,” Dulull says. “Once it comes into the game engine, it stays in the game engine. It doesn’t matter where the original source came from, as long as it is exported in a format that’s readable in Unreal.”

Dulull estimates that for an animated film, filmmakers could save approximately 40% of their budget by working in real time, since they are doing final pixels so there are no render farms rendering CG passes, and there is no compositing pipeline required, either.

When it comes to virtual production and LED volumes, which also use game engines, the cost of using an LED volume should be maximized. Rather than shooting one or two shots, he recommends shooting 70% of your footage because that can be amortized across a show or film—after all, you are paying to use the volume for the entire day. Compare the cost of using the LED volume to sending an entire crew to a location, not to mention there are no daylight limitations or weather issues to contend with, and this option seems obvious.

While the advantages are many, there are disadvantages as well to using a game engine for film content creation. The biggest one, in Dulull’s opinion, is mindset—some animators may not want to work in real time. But that is changing. Another disadvantage to using a game engine: “It’s a video game engine, and it’s going to break, especially if you move to a new version,” Dulull says.

For instance, Haz Film started and finished the animated movie Rift in UE 4.26 and then moved to UE 5 because it had features like Nanite and Lumen that were too attractive to pass up. “But UE5 was a whole new system, so all the stuff you code, all the systems and pipeline presence you create will most likely break because Epic has taken away that feature and replaced it with something better,” Dulull explains. “It’s a scenario that often happens in game development industry, whereas with traditional film workflow, you don’t have that; once you’ve shot it, it’s already in the can.”

Rift took about two years to complete, with several other projects also falling within that time frame. Currently, the Haz Film group is working on the Rift video game.

Haz Film’s Rift game and film are stylized but still require computational power. “If you want to work in the real-time space, you need the hardware to drive it,” the filmmaker says. “It’s all about your GPU and having good hardware space, too, for the cache files.”

For Rift, the group used an Nvidia RTX A6000 AIB, rendering the entire movie on one RTX board. But at this year’s GDC, Dulull announced a partnership with AMD to use the Ryzen CPU (Ryzen 9 7900X 12-core processor) and the Radeon Pro GPU (W6800). Blackmagic Design’s DaVinci Resolve was used for all the editorial, and then it was converted from sRGB to linear color space, since this is a TV film. “We’re not even transcoding proxies, so I can go back if I need to and make changes,” says Dulull, who is now running UE5 on the latest Asus Studiobook laptop.

The bottom line: The equipment overall is relatively inexpensive, resulting in smaller teams that are able to make their own games, movies, or immersive content, since they are not restricted to having racks and racks of servers.

Dulull’s work tends to fall into the sci-fi realm because that is what he likes best. With sci-fi, there is a lot of creative license, he notes, perhaps making it an easier genre to work with in a game engine. Today, though, he doesn’t believe genre matters when it comes to using a game engine.

Dulull credits the opportunities his company has been afforded from working in real time. Game engines have evolved and are less buggy now and easier to work with, and the tools are more sophisticated, he says. And now connected devices like iPads and smartphones are easier to use with the engines.

Without question, game engines have democratized the film industry, giving those with the creativity, drive, time, and passion the chance to break through what was once a technical barrier. “I remember about 15 to 20 years ago, everyone kept saying, ‘The film industry and the game industry, they’re coming together. They’re pretty much overlapping.’ Looking back, though, when compared to today, they were not even close and not even in the same realm,” Dulull says.