A few days ago, Oscar history was made when a film, made on a paltry budget with just a handful of staff compared to Hollywood standards, won the coveted Oscar for Best Visual Effects. While the movie’s star, the CG Godzilla, is the Goliath in this story, its filmmakers are the Davids. The VFX team attributes their success to a streamlined workflow and having to work smart and efficiently in a country (Japan) where film budgets and staffing are a fraction of what they typically are in Hollywood. Their story, like their win, will forever be part of Oscar history. And sometimes the story becomes the story.

This is the tale of the monster that destroyed Hollywood and has become a legend. It happened during this year’s Academy Awards. That’s when the gargantuan monster—well, its creators and handlers, to be precise—crushed it at the Academy Awards, winning the Oscar for Best Visual Effects over some of the industry’s biggest and most highly-acclaimed VFX teams. (The film’s trailer can be found here.)

To truly appreciate this feat, we need to first turn back the clock. The prehistoric, amphibious Godzilla was hatched several decades ago in Japan, and over the years has appeared in dozens of films, not to mention TV shows, comic books, video games, books, and so on. In the monster’s early years, it was the star of many Japanese B-type movies with kitschy-looking effects. Over the years, though, the massive T. Rex/stegosaurus-like creature Godzilla began to evolve, brought to life through various means—from a person in a rubber suit, to stop motion, animatronics, and CGI.

And during that time, the rampaging reptilian faced off against many other monstrosities—the ancient ankylosaurus named Anguirus, Monthra, the three-headed Ghidorah, the giant crustacean Ebirah, Hedorah from space, Megalon, Mechagodzilla, Destoroyah, and King Kong. Nevertheless, those encounters led to some epic, city-destroying battles. The kitschiness was part of the attraction. (A montage of movie posters over the years showing Godzilla’s evolutionary look can be found here.)

The Godzilla franchise got a high-tech, polished makeover (even a monster needs to look its best in Hollywood) with an infusion of CG in 1998’s Godzilla. Goodbye, kitschiness. Despite grossing $379 million worldwide and becoming the third highest-grossing film that year, its profit was negligible after taking into account production costs of $130 million to $150 million and marketing costs of $80 million. As a result, planned sequels at TriStar were cancelled. But you know the old saying, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.” And Hollywood did just that some years later with a Godzilla remake in 2014, giving it all the star power possible. They seemed to be on to something.

In the US, Godzilla’s legendary status dipped with Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019) but bounced back with Godzilla vs. Kong (2021), earning $470 million worldwide on a budget of $155 million to $200 million. Everything about the films was big—the beasts, the destruction, the effects, the budgets. In King of the Monsters, leading studios DNeg, MPC, Method, and Rodeo generated epic battle scenes. In Godzilla vs. Kong, the talent continued to be top-notch, with Scanline, MPC, Luma Pictures, and Weta Digital handling the weighty effects, from monsters to mayhem. Alas, neither film made the Oscar short list.

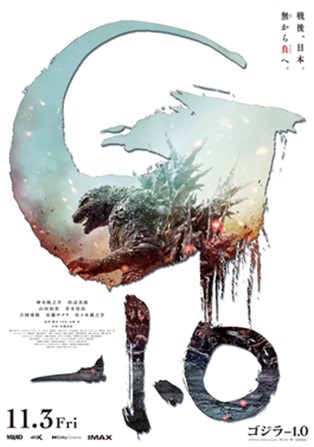

Meanwhile, Japan’s Toho continued to cash in on the franchise, eventually ditching kitsch for digital pizazz. In December 2023, Toho released Godzilla Minus One, the 37th Godzilla feature (33 from Toho, one from TriStar, and three from Legendary/Warner Bros.) and according to the story that will surely become Hollywood lure, the director himself hand-delivered the film in time for Oscar consideration. Not only did the film make the sought-after Oscar bake-off, but this foreign film advanced to be a finalist in the Visual Effects category (dominated by Hollywood) and then, against all odds, took home the statuette.

A remarkable feat, indeed. And, a remarkable story. But what is truly remarkable is the story of how they did it.

First, the who. In a unique scenario, the writer, director, and VFX supervisor on the film is the same person: Takashi Yamazaki. He shared the VFX supe title with Kiyoko Shibuya (also a producer on the film), making her the third female to win the VFX Oscar. Also receiving a statue for the film is veteran CG director Masaki Takahashi as well as Tatsuji Nojima, an effects artist/compositor making his mark at just 25 years of age.

The film had some great competition this year, and some people were surprised at big productions that did not make the final cut, with some left off the VFX short list (Barbie, Poor Things, Dungeons & Dragons, Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania, Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, Transformers: Rise of the Beasts, and Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, to name a few). Yeah, everyone has their favorites, and each year there is disappointment/disagreement among moviegoers and industry practitioners, me included. Were the Academy voters drawn to the story behind the making-of Minus One, and did that tip the scale in favor of these filmmakers? I am not trying to take anything away from their work. It’s just that in this particular instance, their story is, well, a real Hollywood tale.

The movie, which has 610 VFX shots, was made for less than $15 million by a group of just 35 artists. (Reports vary on the cost, as is typical, putting it at between $10 million and $15 million, with a quarter to a third of the film’s overall budget said to have been dedicated to the VFX.) The work was done at Shirogumi’s Chofu studio under the supervision of Yamazaki and direction of Shibuya over an eight-month period. In comparison, Godzilla vs. Kong, which had an army of VFX artists from four main vendors that contributed approximately 990 VFX shots, was made with a budget that was reported to have been between $155 million and $200 million. (Also, some assets from the previous films were reworked/reused in certain instances.)

While those effects were impressive, they failed to get an Oscar nomination, let alone a win.

Let’s face it, the cost of a VFX-heavy film such as Godzilla vs. Kong is going to be expensive—at least according to Hollywood expectations. Visual effects are not cheap—usually. Consider the budget for this year’s finalists that became fodder for Godzilla:

- The Creator, $80 million

- Guardians of the Galaxy Vol 3, $250 million

- Mission: Impossible–Dead Reckoning Part One, $291 million

- Napoleon, $130 million to $200 million

In fact, the last movie to win the VFX Oscar with a budget like Minus One was Ex Machina in 2015—also considered an anomaly. At the other end of the spectrum is last year’s winner, Avatar: The Way of Water, with a budget of $350 million to $400 million.)

And now, the how. The software used on Minus One is really no different from what was used on Godzilla vs. Kong and, frankly, most other VFX feature films: Autodesk Maya, SideFX Houdini, and Foundry Nuke. But as we all know, VFX studios create proprietary tools and plug-ins, as well. So, what was the key?

For years, the VFX industry has been rife with complaints by artists of long hours and harsh working conditions, leading to a call to unionize. However, in an interview with IGN, Yamazaki says that was not the case on Minus One, for which everyone had their weekends and not many late nights. It was the computers that had the late nights, he said, especially when it came to the water simulations and the city destruction. And there were a lot of water shots—even more than was originally planned, thanks to the work by artist/compositor Nojima, who is said to have built his own supercomputer at home for the project. All told, the water sims totaled about 1 petabyte.

He attributes the how to a streamlined workflow and fast shot approval process.

Yamazaki states in that interview: “What I don’t want to do is give studios and producers the idea that ‘Hey, you can do it cheaper, with less people!’ I don’t want the VFX industry to go on this weird tangent.” He did note the team made some discoveries about the approval process and the feedback cycles. In their case, he was on-site the whole time, on the same floor, as the VFX artists and could just go to someone’s monitor, approve things, give them direction, and get another feedback loop in the time that others have to send dailies or wait for notes to show up. As a result, they were able to eliminate certain inefficiencies. “But I don’t want this to be misconstrued as ‘we can do more with less’ because that was not the case. Our situation was unique, given how I was situated in the larger scheme of the overall production. And the fact that I had a clear goal, more perhaps than other directors, because of my VFX background. There are good inefficiencies and bad inefficiencies. We focused on the approval process in different ways to streamline certain aspects of the VFX pipeline,” he further stated in the article.

Yamazaki has also said that keeping the work in-house and not outsourcing it to third parties further saved time and money by not having to rework shots and on redundancies among teams.

Kudos to Yamazaki and his team on a good job. Some have called it the best Godzilla movie yet; others called it one of 2023’s best films, praising the story and the effects. It scored a 98% on Rottentomatoes. (A short behind-the-scenes video can be seen here.) Overall, was it an Oscar-winning VFX production? Some say yes, others not so sure. Count me among the latter.

Nevertheless, there is a good story here, one beyond the film plot.

Meanwhile, as we have learned in the Godzilla franchise, it’s hard to keep a good monster down. Adam Wingard, who directed Godzilla vs. Kong, is hoping that Godzilla continues to receive the love from audiences and critics. After all, at the end of this month, Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire, which he directed, will hit theaters. Just don’t expect the same low-budget story this time; reports set the cost of the production at $185 million to $200 million.