Constantly coming up with new content to feed the seemingly insatiable appetite of entertainment seekers is no easy task. But hey, people, and lots of them, love games. So, why not use video game IP and turn it into a movie and/or series? It wouldn’t be such a bad idea if studios could get it right, but too often they don’t.

(Source: Pexels, Markus Spiske)

“Source Code is not time travel. Source Code is time reassignment. It gives us access to a parallel reality.” –Dr. Rutledge, “Source Code,” Universal Pictures, 2011

Every so often, you find yourself walking down the street, feel a squish beneath your foot, and know even before you look… you’ve stepped in it. That’s about what it felt like when we “reviewed” a movie, Borderlands, and the series Fallout with a couple of intellectual (really smart) friends. Both came down on us like a sledgehammer, saying the two really weren’t “decent” video game adaptions. One of the two was the founder and past editor of BabelTechReviews and the other knows more about the computer graphics industry than anyone should know.

Yeah, that smart.

When it comes to films/shows, we probably should have anticipated the two were derived from game IP, since more than 26% make their way to the big or home screen. That made us wonder why the film/show industry either can’t come up with its own storylines or has such a hard time starting with a successful video game storyline and changing stuff to weave it into a film/show series but just can’t seem to attract eyeballs and make a profit. The potential audience has to be there because, according to Exploding Topics, more than 3.3 billion folks on the planet, or about half the population, are active video gamers. So, we decided to get a new look at gaming.

First of all, the industry is a helluva lot different and bigger than in the days we worked with the Tramiels and Atari.

Let’s start with the obvious…. The industry has changed/grown in almost every way—the variety of games, playable devices, players, quality, earnings. We were surprised, and a little demoralized, to see that the gaming arena outstrips not just the content industry but also the music industry, and the two combined aren’t even close to the gaming industry. The industry is projected to generate about $193 billion this year and is projected to surpass $426 billion by 2029. In comparison, the music industry delivers $26 billion-plus and the global movie industry should sneak in with about $100 billion.

Gaming has come a long way since the days we’d walk into the developer area and folks were asleep under their desk after pulling “another” all-nighter or sitting there buzzed on double espressos and surrounded by Twinkie wrappers. Yeah, that won’t happen again. The new breed of developers is the same but different from older developers.

According to GDC (Game Developers Conference) organizers, the younger crowd is 157% more likely to support unionization, especially in light of the latest rounds of layoffs as well as the impact of generative AI on gameplay and player data acquisition/usage. We see AI from both sides of the screen.

There are a lot of similarities (and differences) in animation and game development. But Jeff Katzenberg, former head of DreamWorks Animation and The Walt Disney Studios, has noted that 90% of the cost and work involved in animation could be replaced by AI. We haven’t heard Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s boss and the leading producer of GPUs for gaming and content development, address the issue, but the two forms of entertainment are just too similar—and so are the costs.

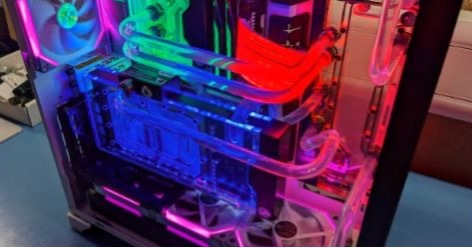

We would classify both of the experts as serious gamers. They’ve both built monster computers that can handle even the most processor-intensive game flow to enable them to flawlessly play through the night and change game scenarios to try a growing range of activities and outcomes.

Game AI can make high-concept storylines even more compelling. It can make small characters more complex, more dynamic, more spontaneous, and more natural. It will also enable them to try different/alternative scenarios in the games to achieve the successful conclusion they want.

As for whether AI will be able to write a good game storyline, the question isn’t can it but should it. It’s similar to the quandary of AI writing a good movie. A soulless machine might write something decent, but does it have emotion, empathy, feeling? Games are even more important because you’re not just watching the content flow by, you’re in it. You’re controlling, changing, guiding it.

When it comes to real VR, these advanced capabilities won’t be just nice, they will become vital. VR has been a work in progress for years. It’s not here yet, but it is improving. The games are becoming better, more real, and more immersive with each new generation. At the same time, the hardware has made major improvements in recent years, and it is becoming more affordable. When the two do arrive, you’ll have a difficult time knowing which world you’re in until you look in a mirror. If you see the headset markings on your face, you’re back in the real world.

But, video games are more than just about power systems and VR headsets. We know guys think video games are a guy thing, but gawd are they wrong. Video games may be one of the few forms of entertainment that is enjoyed by young and old, males/females, local and globally.

There are more than 3.3 billion video game players worldwide. Across all ages, video game players identify as about half female (46%), half male (53%), and 1% don’t pick sides. The average video game player isn’t some young punk, he/she is 32 years old and has been playing video games for 21-plus years. In the Americas— and it’s probably similar the world over—26% are under the age of 18, 35% are 18–34, 11% percent are 45–54, and 14% are 55 and older.

In other words, age is just a number, kid, because the Gen Xers (40–54) and baby boomers (55-plus) account for about 36% of the gaming population, and they’ve played the best and worst before gaming was cool. And she’s just as good, and probably better, than he is.

It turns out she (and he) live/play across the globe, speak a wide variety of languages, play on a variety of platforms, and are partial to specific genre. The smallest percentage of gamers are like our friends, who prefer to buy and download games for their systems. Far more prefer Xbox (Microsoft), PS4 (Sony), iOS, Android, and Switch (Nintendo). But once games moved to the cloud, they immediately became the entertainment of choice for iPhone and other smartphone users.

The US and China have the most video gamers per country, but Asia-Pacific clearly dominates sales. Asia-Pacific represents the largest market, thanks to China, which is both the biggest potential audience as well as the largest content producer (Tencent with more than $7 billion in revenues). Sony is the second-largest producer with more than $.5 billion in hardware and software sales, followed by Apple, which isn’t huge in the game development area, but the Apple Store contributes more than $3 billion in Mac/iPhone game sales/subscriptions to the company’s bottom line. Microsoft is in fourth place after dodging antitrust issues and successfully adding Activision Blizzard to their lineup.

Obviously, they’ll be adding their AI technologies into the game and are looking long and hard as to how they pare down development costs with the technology.

Cloud and mobile gaming have quickly become the largest and fastest growing market segments. Mobile games have given iPhone (and other smartphone users) something to do beyond creating TikTok videos and taking selfies.

According to DFC Intelligence, more than 3 billion-plus people are paying video game users and about 44% only use their smartphone for gaming. It’s obvious that video gamers want to take their games with them everywhere, and the development of game controllers for your smartphone delivers the action folks expect today. To handle the needs of the console players who want to/need to connect with their games when they aren’t in front of their large screen, several third-party producers have also developed controllers to put all of the gameplay in their hands, regardless of where they are.

And since everything was being stored in the cloud and delivered over the Internet, the logical question before the pandemic was which of the giants—Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Apple—was going to reshape the industry and become the “Netflix of gaming.” So, while each of them was trying to figure out how they could retain their gaming revenue stream and capture digital natives, Netflix surprised the gamer folks and made Wall Street question management’s sanity by announcing Netflix Games.

They set up a Netflix Games division (structure is important), acquired a decent roster of gaming studios, and started creating games based on some of their shows/movies. Whether you play the games on your big home screen, computer, or smartphone, they didn’t care, as long as you regularly visited Netflix for any/all of your entertainment.

A helluva move! Everyone in the streaming video industry, and their stakeholders, has been sweating the huge problem of churn. It’s relatively easy and painless to sign up with a service, watch what you want of their new stuff, drop them, move on to a new set of shows/movies, and then maybe eventually return.

You know, how hard it is to give up a couple of games you’re really into? Yeah, 50 or 60 hours of play is just a good start—especially when you take a break from the trials, tribulations, battles to watch a horror/shark flick, K-drama, or anime story and never have to leave your service.

Nevertheless, there’s a very low chance you’re going to take a break from gaming to watch a film/show based on video game IP, according to film/show industry analyst Stephen Follows.

Shows on video game IP have proven to be anything but successful for studios, networks, streamers. Follows takes us back to the original discussions we had with our video game experts. Sure, some adaptations like Mario Bros., Sonic the Hedgehog, and a few others do well at the box office and on the home scree—but not many. According to Follows, most video game adaptations aren’t very good. In fact, they’re often extremely very bad. Almost universally, critics pan them, and audiences shy away from them.

Of course, there are still people like us who didn’t know a film/show was based on a video game, and we still wonder WTF? when we can’t make sense of the project.

But as Colleen Goodwin said in Source Code, “The program wasn’t designed to alter the past. It was designed to affect the future.” That’s probably why Sony does so well with its film and game divisions. They each do what they do best without trying to mess with the other’s business. It’s tough because everyone knows the other guy (or gal) has a sweet thing going there and they want/deserve a piece of it.

Sorry, even we know a great movie/show is a great movie/show, and a game… is something else.

LIKE WHAT YOU’RE READING? INTRODUCE US TO YOUR FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES.