Summers just wouldn’t be the same without a Transformers film with all its explosive action. For a decade and a half, audiences have been introduced regularly (albeit not yearly) to a variety of bots that can transform into vehicles. And then they encounter dire situations where the world as we know it is in peril, and they can only save humans and the Earth with the assistance of some human they encounter. This year, the film franchise gives us animal bots called Maximals, who team with the Autobots to, once again, save the world from the biggest baddie of all in Transformers: The Rise of the Beasts.

Many remember the plastic toy robots from Hasbro that, with twists and bends at key joint locations, would turn the bots into something totally different—a car, tank, spaceship, and so forth. Their popularity was reignited for a new generation after Director Michael Bay introduced theatergoers to the Transformers movie in July 2007. In that Paramount Pictures/DreamWorks SKG’s blockbuster, we were introduced to two sets of robots: the good Autobots, who shape-shift into cars and trucks, and the baddies, the Decepticons, who change into military vehicles.

Most of the time in that original film, the robots were computer-generated—with a lot of CG parts. For example, Optimus Prime, leader of the Autobots, comprised over 50 parts in its toy form; in that Transformers film, the bot had over 10,000 CG parts. The trick then, as well as in the latest Transformers film, Transformers: Rise of the Beasts, is that each character is essentially two characters in one (a bot and a vehicle), and modelers have to determine which pieces are essential to building both. Then, the parts have to be animated.

In that original film, a large part of the work was handled by ILM, along with Digital Domain and Asylum. The film received an Oscar nomination for Best Visual Effects. A string of sequels followed from 2009 to 2018—Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (June 2009), Transformers: Dark of the Moon (June 20011), Transformers: Age of Extinction (June 2014), Transformers: The Last Knight (June 2017), and Bumblebee (December 2018).

Another Transformer film, Rise of the Beasts, was released this summer and is a sequel to Bumblebee, set after the events in this last film. It is the seventh installment in the live-action film series and is described as a stand-alone sequel to Bumblebee and a prequel to the original Transformers film. Another movie in the franchise, Transformers: One, an animated prequel, is expected next year.

In the past, ILM helmed the visual effects and CGI work on the Transformers films, but for Beasts, that work fell to MPC and Weta FX. ILM will return to provide the animation for One. Gary Brozenich served as production VFX supervisor on Beasts.

Beasts is set in the 1990s, and introduces the Maximals, an advanced race of Cybertronians, who had come under attack from the planet-sized, planet-eating dark god Unicron, thousands of years earlier. Then as now, Unicron searches for a certain bit of technology that opens portals through time and space. Back then, the Maximals escaped the siege from Unicron’s Terrorcons and army of Predacon scorpions, and, led by Optimus Primal, fled to Earth, where they remained hidden from sight—until now.

As the name suggests, Beasts features transformative creatures that take the shape of animals such as a peregrine falcon, mountain gorilla, cheetah, rhinoceros, and so forth. When a statue is accidentally broken, it reveals half of a hidden portal key to the technology Unicron is seeking, and that releases a signal to Earth. The signal attracts the dark god’s Terrorcons and Predacons. (The other half of the key, in case you are wondering, is in Peru, where the story later picks up.) To save Earth, the Autobots and Maximals unite against Unicron and his henchbots.

MPC effects work

The effects work from MPC was overseen by MPC VFX Supervisors Richard Little and Carlos Caballero Valdes, and MPC Producers Cindy Deringer and Nicholas Vodicka, who worked with more than 1,000 artists and production crew from six MPC studios across the globe. In all, MPC delivered 863 VFX shots for the film. They worked on 18 characters, many of them new to the film franchise including Unicron, in addition to various sequences. They also handled design work.

Back in 2021, Brozenich met with the filmmakers to plan how they would bring the director’s vision to life for this new Transformers film. MPC’s on-set crew traveled to Montreal, New York, and Peru to gather data from the shoot locations that would be used to facilitate the visual effects work.

MPC’s visualization team, under the supervision of Abel Salazar, worked with Brozenich and the director, Steven Caple Jr., to help craft some of the more dynamic sequences that would be used in previs. To provide a smooth transition into visual effects, they generated more than 2,000 postvis shots, which the VFX teams built upon. (Halon Entertainment and The Third Floor also provided visualization services for the film.)

Concept art for the characters was created by the production’s art department, and as production continued, some designs were further developed by MPC’s art department, under the leadership of Leandre Lagrange, art director. This included details of Unicron’s design, Arcee’s face design, Optimus Prime’s weapons, and various holograms including Arcee’s scan hologram in the film.

MPC, as well as Weta, crafted new characters and rehabbed those from previous films. Among the 18 characters tasked to MPC were: the female Arcee, the ever-present Bumblebee, the newcomer Mirage, Maximal leader Optimus Primal, Autobot leader Optimus Prime, the formidable Maximal Rhinox, the larger-than-life invader Unicron, and Unicron’s assistant Scourge. Previously, the bots were hard-surface creations of metal plus rubber bits. For this film, though, the Maximals, which transfer into animals, have feathers and flesh integrated into their metal exteriors.

To facilitate the character transformations, MPC developed a new proprietary tool that enabled the animators to slice, separate, and transform the geometry on a model, in any given shot and on any asset. MPC says multiple departments—R&D, animation mechanic technical directors, and CG lighters—united in making the transformations successful.

In addition to character work, the MPC team also tackled sequences including the one at the start of the film in New York and the abandoned warehouse where the main human characters meet the Autobots. They also handled a battle at Ellis Island, a switchback mountain chase, and the pivotal sequence when the Autobots meet the Maximals.

The MPC environments team constructed multiple large-scale, full-CG sets as well as digital set extensions, including jungles, mountains, and bustling cities. The MPC art department even worked on concepts for volcano environments.

One of MPC’s biggest tasks in terms of environments was to turn back the clock of present-day New York City to 1994. And indeed, a lot of changes to Manhattan has occurred in that time. To accomplish this reversal of time, the team created a large CG build of Manhattan, using photography and footage from the 1990s as reference. Some of the images of the skyline were provided by New Yorkers that Little had worked with on the shoot, some of which came from personal family collections.

The Williamsburg Bridge, which is heavily featured in the sequence when Noah, the new human hero, first meets the Autobots. For accuracy, the bridge was photographed and scanned prior to being re-created in CG.

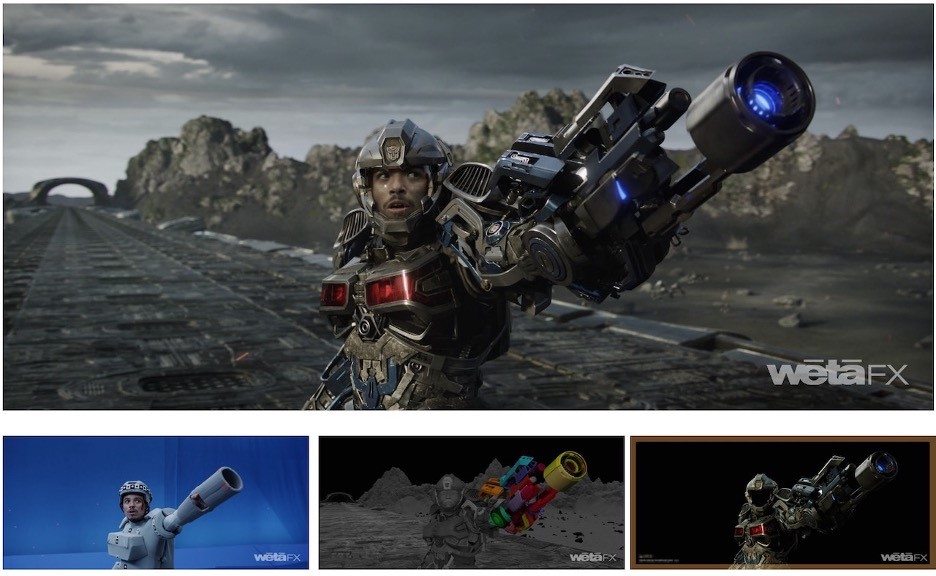

Weta’s effects work

Weta created 460 VFX shots for the film—60 in the cold open sequence and the remaining in the third act. Weta sets up the story, taking audiences back a few millennia to the destruction of the Maximals’ home planet. This required choreographing the sequence through extensive previs and motion capture.

Like MPC, Weta crafted a number of Maximal creatures, including the Maximal leader Apelinq, who sacrifices himself in the establishing sequence so that the other Maximals could escape the besieged planet before it was devoured by Unicron.

The creature work for Transformers: Rise of the Beasts was daunting due to its scope and complexity. Taking into account the robot and non-robot forms, Weta FX animators were dealing with over 30 hero creature rigs on the show. “Our rigging department had to go full-court press early on in the show to get animation puppets for all the Transformers into the animators’ hands, and then to do all the detailed rigging of the hero creatures,” said Matt Aitken, visual effects supervisor at Weta.

To get the necessary sense of scale and complexity into the huge Transformers, the puppets had primary, secondary, and tertiary layers of controls that were available to the animators. This enabled the characters to not just move as a whole, but also move every individual wheel; panel nuts and bolts could also jiggle and turn, adding a lot of visual complexity to close-up shots.

The Maximals had the additional complexity of fur, which had to be stiff, like steel bristles, but still needed a subtle level of secondary dynamic motion.

Like MPC, Weta crafted a number of Maximal creatures, including the Maximal leader Apelinq, who sacrifices himself in the establishing sequence so that the other Maximals could escape the besieged planet before it was devoured by Unicron.

The creature work for Transformers: Rise of the Beasts was daunting due to its scope and complexity. Taking into account the robot and non-robot forms, Weta FX animators were dealing with over 30 hero creature rigs on the show. “Our rigging department had to go full-court press early on in the show to get animation puppets for all the Transformers into the animators’ hands, and then to do all the detailed rigging of the hero creatures,” said Matt Aitken, visual effects supervisor at Weta.

To get the necessary sense of scale and complexity into the huge Transformers, the puppets had primary, secondary, and tertiary layers of controls that were available to the animators. This enabled the characters to not just move as a whole, but also move every individual wheel; panel nuts and bolts could also jiggle and turn, adding a lot of visual complexity to close-up shots.

The Maximals had the additional complexity of fur, which had to be stiff, like steel bristles, but still needed a subtle level of secondary dynamic motion.

For the character animation, Weta used mocap, making, that motion feel robotic and consistent with the established Transformers style. However, that was just one small part of the animation process—these characters had to transform into their alter egos. Weta performed these complex character transformations, particularly for Optimus Prime, Bumblebee, and Mirage, that paid homage to the way the original toys transformed. “The transformations were the single most complex aspect of our work,” Aitken said. “Every individual transformation is bespoke, a mini project unto itself.”

The animators began working on the transformations immediately on turnover, and the last two or three shots Weta delivered were transformation shots. Aitken said the key to making these shots work was the time and effort the group put in up front in developing the tools necessary to achieve the transformations, even though that delayed the start of detailed animation until it was almost too late.

“This level of hard-body articulation work was new to the facility, and coming onto the show, we didn’t have all the tools that we would need,” Aitken explained. The group extended its Mesh Tools workflow so that animators had complete control over every component of the robots. They could not only freely transform every panel, piston, screw, and spring and simultaneously control its visibility, but they could also cut up component geometry into smaller pieces where required. As a result, this was all completely publishable and bakeable. So once a transformation was animation-approved by the client, it could be faithfully replicated in the subsequent hero geo renders.

“When we first showed the animation for Bumblebee’s triumphant transformation from off-road Camaro to robot sliding up the ramp to the bridge, we weren’t sure if we had strayed outside of ‘Transformers canon’ in having the robot arm appear first assisting the slide,” said Aitken. “The response from the filmmakers was overwhelmingly positive, concluding with, ‘We have to put that shot in the trailer!’”

Another big challenge for the animators was enabling the robots to convey all the subtleties and nuances of human facial performance for moments such as in the cold open when Apelinq entrusts the Transwarp Key to Optimus Primal and turns to face Terrorcon leader Scourge alone; or in the final battle as Mirage succumbs to Scourge’s blasts while protecting Noah.

This was done by leveraging Weta’s suite of proprietary tools to solve unique creative problems, including the application of facial performance capture to rigid-surface robotic models. “Our facial rigs had to transcend their hard-surface nature,” Aitken said.

Without question, Weta has some of the most talented facial animators in the world, but they almost always work with fleshy faces. This would be different. The group decided from the start to set up the facial puppets to replicate the standard UI the facial animators are adept at driving. Aitken explained they leaned heavily on their existing FACs pipeline and used their Genman human face as an underlying driver for the rigid primate faces. “Conceptually, the setup was as if we had morphed a human face to fit within the inner envelope of a giant robot’s face, and then covered it in the hundreds of individual pieces that form the exterior face of Apelinq, Primal, or any of the other robots. This method proved very successful for drawing on our knowledge and experience with facial animation to create incredibly emotive performances, with very subtle and believable nuance not generally seen in Transformers films,” said Aitken.

There were technical issues with the large number of intersections of rigid-face geometry, due to the “flesh-driver” face beneath not obeying any sense of collision with the rigid pieces upon it, Aitken noted. To resolve this, a final clean-up pass was made by the facial animation team, as they manipulated individual face pieces where required, while retaining all the emotive power of the performance.

Due to the size and complexity of Unicron, the character was shared with MPC, as both studios focused on his immense size, scale, and the physics of his attacks, ensuring that they appeared plausible. As noted earlier, Unicron is the size of a planet, giving rise to challenges that were both technical and artistic. The basic unit of work at Weta FX is the centimeter; had worked the artists worked with Unicron at 1:1 scale, they would have been dealing with substantial precision errors. So the layout department established a workflow whereby all the Unicron shots were done at a reduced scale to make him more manageable.

In space, there is no atmospheric haze for depth cueing to explain Unicron’s size, so the team developed other approaches to establish his scale early in the film. These included careful camera placement, framing Unicron against the Maximals’ home planet in the cold open sequence and adding micro-textures, implying city lights seen from space, to his surfacing.

Weta then picks up the action in the third act, with an almost entirely digital battle that takes place inside a volcanic crater, an environment that was shared with MPC. In that scene, the only plate footage was from the human character performances. Among the effects work Weta contributed to the film were lava simulations for the scene, in addition to large-scale destruction.

In the shots at the end of the climactic fight in the volcano, when Unicron is closest to Earth and seen directly overhead, “his scale was cheated down massively to assist with the storytelling,” Aitken explained. “If we had maintained his planetary scale in those shots, it would have been impossible to frame up on the entirety of his maw, diluting the menace of his approach.”

Similarly, the scale of VFX simulations where Unicron was interacting with the environment were scaled down “by eye” to achieve the most dramatic read.

Weta further handled a key moment in the third act as the multi-shape-shifter spy Mirage, a transforming Porsche 911 stolen by Noah very early in the film, uses his ability to project multiple versions of himself and transform his damaged body into an exo-suit for Noah. This gives the human Noah the powers and weapons of a Transformer.

In typical fashion, Optimus Prime saves the day from Unicron’s army of baddies, and the human protagonists save Optimus Prime. The portal key has been destroyed, and all the good guys and good bots stand together to continue protecting Earth. At the very end of the film, we find that Noah and the Autobots are asked to assist in a global peacekeeping mission—and the organization behind that mission is G.I. Joe. I guess we know what is coming next—a mishmash in the toy universe.

As detailed in this story, digital content creation is complex, as we have illustrated here in the realm of visual effects. To learn more about the entire DCC industry—the markets, service and tool providers, and technology trends—see JPR’s Digital Content Creation Report.