Pixar has built a film dynasty with its unbelievable library of treasured animated feature films. However, behind the scenes, the studio has one of the industry’s most valued renderers, RenderMan, which made it possible to create all those amazing films. Other studios use the commercially available rendering technology for their projects as well. In fact, Pixar recently celebrated the 35th anniversary of RenderMan, and the renderer is as revered today as it was when it was first introduced, thanks to its team of developers who continue to ensure that their technology remains on the cutting edge. Over the years, RenderMan and the RenderMan team have been recognized for their consequential impact on the industry, with one such honor coming as recent as last month.

What do we think? We all know about the storytelling faculty of Pixar. The company’s creative genius is augmented by its technological prowess that has enabled CG to develop. RenderMan is different from other commercial renderers in that it is developed inside a studio and is production-proven on Pixar projects before the commercial version ever ships. A good deal of CG history has been written at Pixar, by Pixar, starting with a group of visionaries who also had the technological know-how and drive to pull off something quite special—and something with staying power that continually impacts the industry. The Pixar developers often collaborate with Disney Research, which provides tech contributions (for instance, RenderMan’s denoising algorithm came from a collaboration with Disney Research). Hey, that’s what family is for. Speaking of family, ILM, known for raising the bar when it comes to visual effects, also uses RenderMan, although Walt Disney Animation Studios has its own renderer called Hyperion. Thanks, Pixar, for your continual contribution in rendering technology and for making animated feature films a reality all those years ago.

Pixar’s RenderMan gets better with age

Pixar is known for pushing the envelope, both technologically and in terms of storytelling. The pre-Pixar days began with a small, dedicated group of computer scientists whose ambition was to successfully transition filmmaking into a computerized endeavor, with the goal of creating the first animated feature film. The early years were challenging, first at the Computer Graphics Lab at the New York Institute of Technology and then at the Lucasfilm Graphics Group, where the group began developing technology required for their CG work. That included a rendering algorithm called Reyes, which would be the core algorithm for RenderMan for many years. Reyes is short for Render Everything You Ever Saw, and that’s what it did. Simply put, Reyes combined all the digital elements in a film frame into one final image.

It’s rather ironic that technology so closely associated with Pixar today—RenderMan has been used on every feature film and animated short made at the studio—actually predates Pixar’s founding as an independent company in 1986. Loren Carpenter, Robert Cook, and Ed Catmull are credited with developing Reyes at Lucasfilm/ILM’s Computer Graphics Research Group a short time before Pixar, well, became Pixar. Other early visionaries who worked to make RenderMan technology a reality include Tom Porter, Alvy Ray Smith, Pat Hanrahan, Tony Apodaca, Darwyn Peachey, and Jim Lawson.

Alas, George Lucas did not share the group’s vision of making a 3D animated feature a reality, and spun off the group, selling it to Steve Jobs, who bought into the CG feature plan.

“They did some calculations and realized we wouldn’t be able to do that with the computers we currently had, but with Moore’s law, they determined we’d be able to do it in 10 years,” explains Dylan Sisson, RenderMan marketing manager.

So, in the interim, Jobs bankrolled paychecks for the fledging Pixar a number of times, reportedly contributing approximately $10 million of his own money to keep the dream alive. Meanwhile, Pixar sold the Pixar Image Computer as well as created some animated shorts and over 70 3D commercials to keep the lights on (remember the Listerine bottle swinging through the jungle, or the dancing Lifesavers Gummi spots?).

“That was an interesting part of Pixar development because not only did we get money from clients, but we also were able to hone our pipeline and push the technology along while we waited for the amount of compute that we needed to render an actual feature film,” Sisson recalls.

An early version of the Reyes algorithm found its way into cinema history when it was used on Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan in 1984 to render the infamous Genesis Effect sequence, marking one of the earliest uses of CGI in a feature film.

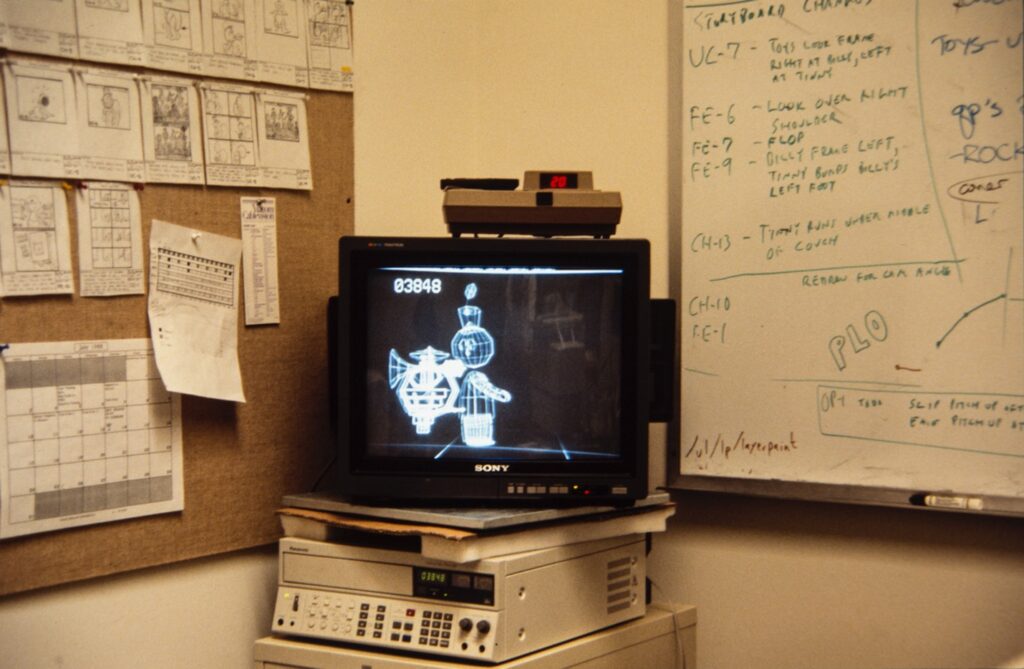

An implementation of the Reyes algorithm, RenderMan got its first debut in the spotlight in 1988. The project: Pixar’s 3D animated short film Tin Toy. The amazing thing about the scanline renderer was its ability to produce photorealistic, film-quality results—which was the purpose of the original RenderMan, since nothing else existed at the time that could produce high-quality images.

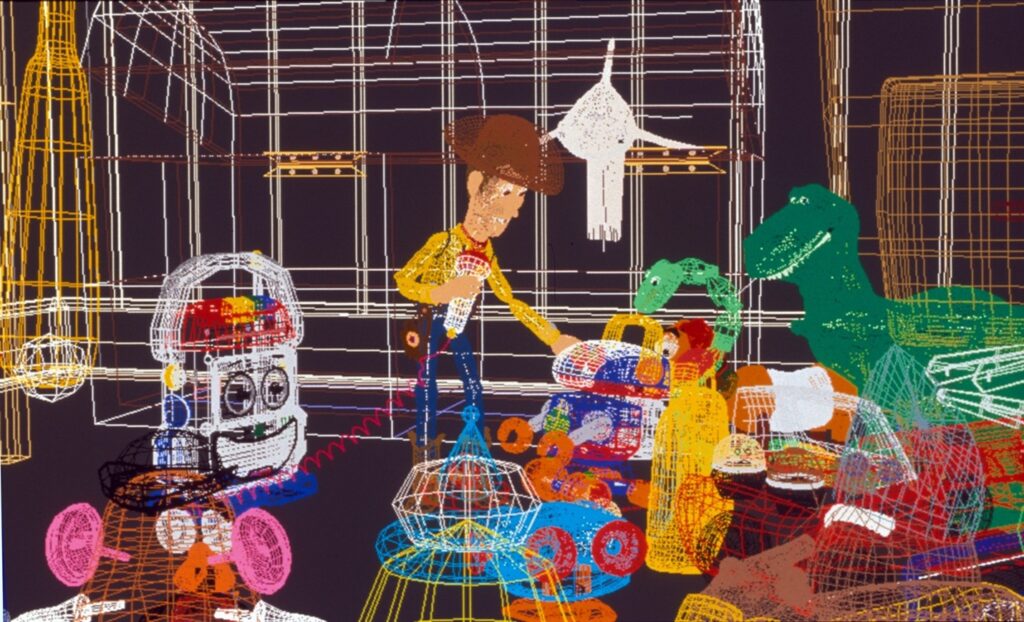

Well-suited for rendering large datasets, RenderMan was used for Pixar’s 1995 Toy Story, the studio’s first computer-animated feature (not to mention the firstallcomputer-animated film). That, no doubt, solidified the software’s stature within the industry. By then, Pixar was selling RenderMan commercially, starting in 1989 with what was called PhotoRealistic RenderMan 3.0.

RenderMan’s history officially starts with publication of RISpec (RenderMan Interface Specification) back in 1988, which was a spec that helped describe 3D data and how to interface with a RenderMan-compliant renderer.

One of the first specifications published by Pixar, RISpec was one of the first ways of doing scene description, says Steve May, Pixar vice president, CTO, which is notable with all the conversation today around USD. That was about the same time that RenderMan was going into use, thanks to the efforts of Carpenter, Cook, Catmull, Porter, and Hanrahan, all of whom were instrumental in different ways to RenderMan’s development, and CG rendering research in general, at the time. Many of the papers written about rendering and rendering research at Siggraph and elsewhere were written by some combination of those scientists.

Says Sisson, the RenderMan Interface Specification, released in 1988, was described as PostScript for 3D, and Photorealistic RenderMan, released in 1989, was a commercial implementation of that specification.

Thirty-five years after its debut in Tin Toy, RenderMan is still one of the industry’s top renderers, as studios worldwide have implemented RenderMan in their CG and VFX pipelines following the commercial availability of RenderMan in 1989. At last count, RenderMan has been used on more than 400 animated and VFX films.

What’s in a Name?

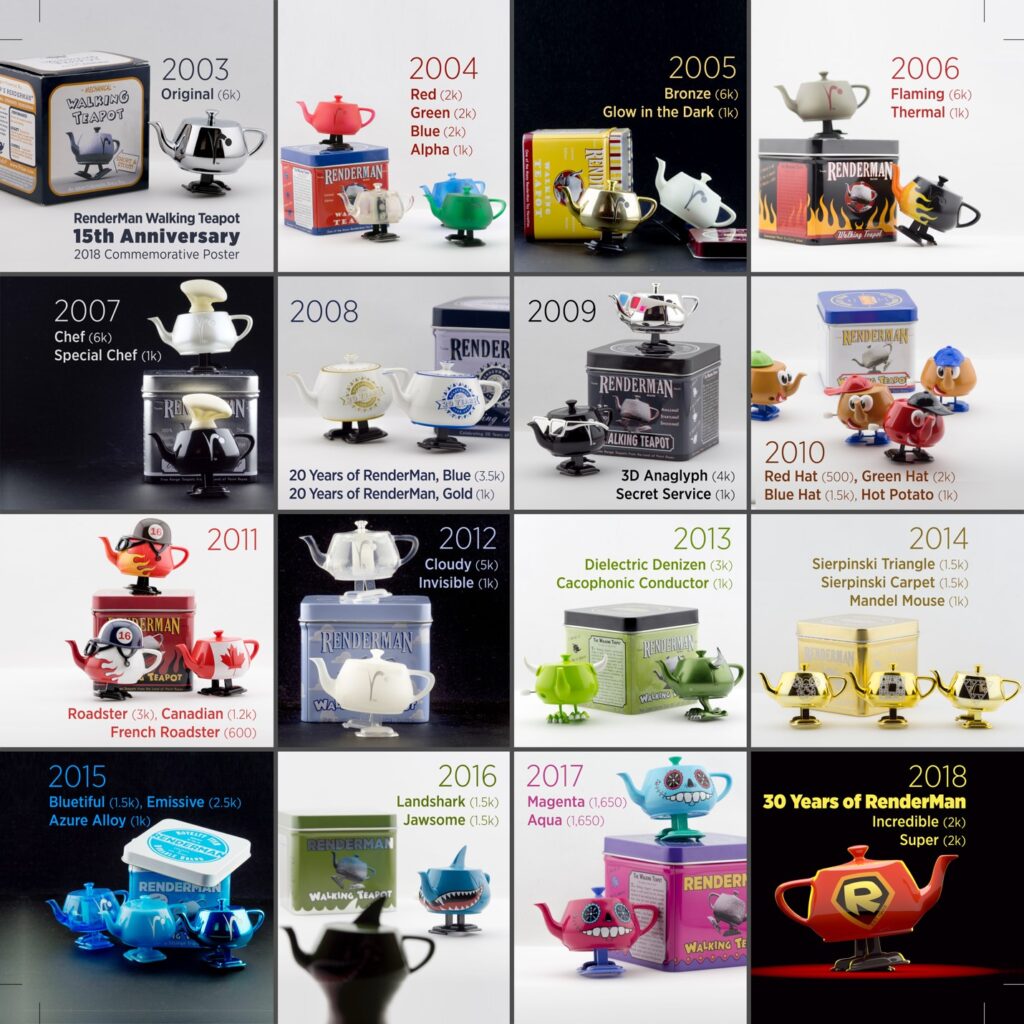

RenderMan was not named after a superhero—its use in that realm came much later. According to Pixar, the renderer got its name from a conversation Hanrahan, a founding employee at Pixar, had decades ago about futuristic rendering hardware so small that it could fit in a person’s pocket, like the classic Walkman, but for VFX.

Within the industry, some have referred to RenderMan as PRMan, which, as May explains, is the name of the executable. So, Photorealistic RenderMan, or PRMan for short, was the name of the RenderMan product that was commercialized.

Reyes was, and had been for a long time, the fundamental algorithm for how the product did rendering. It’s important to note that the renderer was built for a time when machines were far less powerful than they are today. Its strength was that it was streaming in data and rendering as it did so. In short, with Reyes, the RenderMan product could render a complex scene using a relatively small amount of memory and compute power. And, it was the first renderer to have capabilities like motion blur, depth of field, and really good soft shadows and anti-aliasing.

Perhaps surprising, Pixar used fewer than 250 computers to render the first Toy Story film; today, the studio’s render farms are much, much larger and more powerful. With over 150,000 cores on the render farm, artists now can simulate real-world lighting, for instance.

Over the years, visual effects and computer graphics have drastically evolved and become more complex—and so, too, has RenderMan. RenderMan with Reyes was very efficient at tessellating geometry. It had been used for all years, until path tracing became the dominant method for rendering. That is when Pixar developed a new algorithm called RIS, which uses path tracing, to replace Reyes. And so, with version 19, RenderMan was rewritten to become a modern path tracer, able to handle complex global illumination using an advanced system of physically based shaders and lights.

Internally at Pixar, the first big project that used significant ray tracing was the short “Boundin’” (2003), in which the artists made an ambient occlusion pass per frame and used that for a kind of diffuse shading. They also used the tech for the whale’s tongue in Finding Nemo. According to Sisson, once the artists started using ray tracing, they were able to cobble on new, emerging features at the time such as ambient occlusion and physically based rendering.

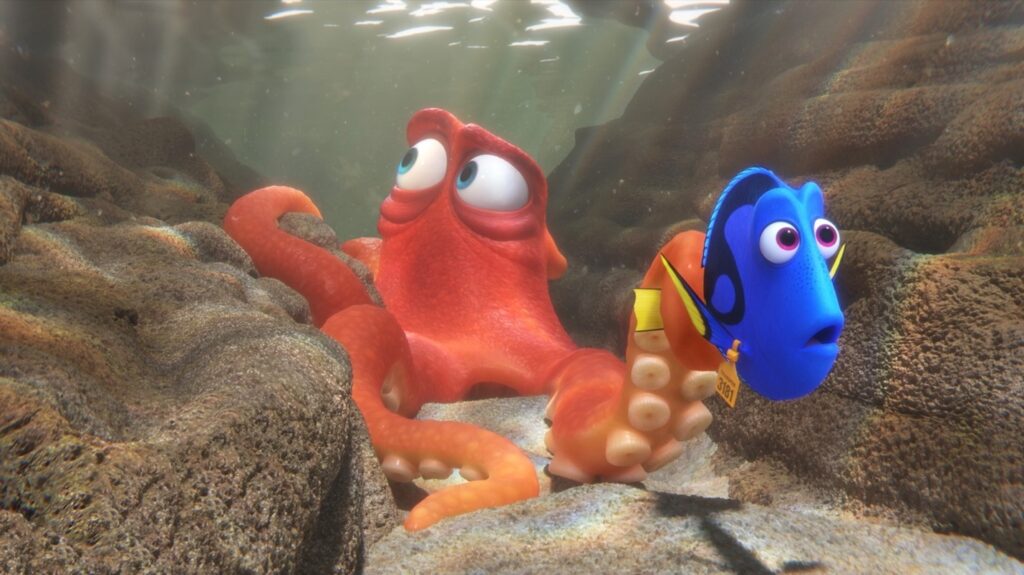

RIS has been in use at Pixar since Finding Dory. Prior to this, it wasn’t computationally possible to do an animated feature film with path tracing, May points out. And, as the algorithms around ray tracing improved, it enabled the automatic generation of complicated lighting effects that, in the past, had to be done by hand at Pixar.

“With Reyes, it was a lot of very complicated, technical, tedious work [to have a bounce light or secondary lighting effect]. It all had to be done by hand with texture maps, shadow maps, and other tricks,” says May.

With RIS, you get global illumination inherently, so things like shadows, reflections, refractions, and caustics all can be done automatically, May adds. As a result, artists didn’t have to worry about a lot of more technical implementations that were required of them because computers were not fast enough.

RIS in RenderMan has evolved and matured over the years with rewrites to the ray-tracing core, new hair descriptions, memory optimizations, and pipeline groundwork, for example.

At present time, the RenderMan team has now arrived at another inflection point. It is still developing RIS, but it is also developing a third architecture called XPU, which dynamically exploits GPUs and CPUs for renders that are much faster—by another order of magnitude—by leveraging parallel computation that is available on the GPUs. Olivier Meisberg, VP of RenderMan products, notes this type of hybrid renderer, which produces the same pixels on the CPU and GPU at the same time, has been a problem the group has been trying to solve for some time now.

XPU is available in both the non-commercial and commercial versions of RenderMan. Internally, XPU is being used for look development within Pixar’s in-house shading tool, Flow. The first phase of XPU delivers a complete feature set for look development. However, some features are not supported yet but will be as XPU matures to replace RIS. So at the time, it is not capable of rendering a Pixar film, but it can be used for interactive look development and other things. But, May says, they are getting close to the fully featured version of XPU. However, it currently has a ways to go to be production-proven, which is always a requirement in the commercial versions of the product.

The goal with XPU is to reach the point of getting a feature-film-quality render back to artists in real time, says May. “That’s the biggest overall challenge we’re trying to solve. It’s actually very, very hard because we’re way off from real time compared to what our final-quality renders look like today. But we’re getting closer to interactive,” he adds.

So, speed sits at the top of the challenge list, and running a close second is finalization, specifically, tools for achieving a stylized, unconventional look—not easily done seeing that all renderers today are grounded in reality because they all use correct perspective. This will be especially important as heavily stylized films are produced. As a result of this movement, Pixar is adding stylized rendering (Stylized Looks) into its tool set.

“Each generation of RenderMan definitely was in response to the demands and needs of the films we are trying to make,” says May, pointing to RIS and its use on Finding Dory, which had a lot of water, caustics, and refractive effects. “But, it was also just as much in response to available technology and techniques that were available for rendering. The ultimate goal is to give the lighting artists better tools to work with.”

Although new releases of RenderMan are not tied to major Pixar films, the features found in the releases are. And, the production needs for a film Pixar is working on can have a big influence on the RenderMan release schedule.

So, to simplify the name game, there is really just one name for the product, RenderMan, although there are three different architectures—Reyes, RIS, and XPU, though the first one is no longer in use. Moreover, RenderMan has undergone many version updates over the years. In April 2023, Pixar released RenderMan 25, which features advanced denoising technology that uses machine learning from Disney Research.

Still raising the bar

In 2023, Pixar released its 27th CG animated feature, Elemental, which May describes as the most challenging the studio has ever made in regard to rendering. For those unfamiliar with the film, the characters are made out of fire, water, and other elements, which required volumetric simulations, and lots of them. For instance, in the case of the fire characters, actual pyro simulations were used; for the water characters, realistic water sims were done. Then, the characters were stylized and artistically directed to make them appealing, both visually and emotionally.

According to May, Pixar has run some R&D tests on assets from Elemental using the studio’s next-generation renderer, RenderMan XPU, and he describes the results as “impressive.”

“We’re discussing which film will be the first RenderMan XPU film right now,” May adds.

Pixar had been releasing a new version of RenderMan every two years, but in an anticipated departure, it is moving to an annual release schedule (with dot releases in-between to address bug fixes, performance issues, driver updates, and so forth), which, May says, will be beneficial to customers. The studio plans to release RenderMan 26 in the second quarter of 2024, which follows version 25, released in April 2023. When the commercial version of RenderMan 26 is released, users will be able to use either XPU or RIS. Besides XPU, RenderMan 26 will feature the next iteration of the denoiser introduced in version 25, along with a new shading system developed at ILM and more, Sisson promises.

AI has been grabbing headlines across the industry this past year, and Pixar is well aware of the advantages it can bring to the table. After all, the denoiser in RenderMan 25 is based on machine learning. Sisson says the RenderMan team continues to look at specific areas where it can implement AI technology within RenderMan but are in the “newbie stage” of exploration, he adds.

“There are tools that do AI texture generation or 3D scene building even now, and we’re happy to consume that data and give you some even better images back. But for us right now, it’s not part of our main road map at the moment,” Sisson says.

Pixar has been creating amazing films over the past decades, most of which have been recognized with various industry awards and accolades, including Oscars, and at the heart of their visual excellence is RenderMan. The renderer has also proven its mettle in Oscar- and other award-winning films from other studio users as well, including ILM and MPC, which have issued requests for certain features, like volumes, which may end up in a new release of the renderer that benefits Pixar as well as other users. Outside the film world, Pixar counts NASA as a client, which uses RenderMan to visualize their datasets. NASA, too, had a certain request, this one concerning the diffuse extinction coefficient, which didn’t give them the flexibility to render the moon correct. So, Pixar added a feature to the shader that anyone can now use to render the moon with the proper extinction coefficient for the diffuse variable, says Sisson.

Today, Pixar’s RenderMan team comprises over 30 people who are located around the world (Seattle, London, and Emeryville and Santa Cruz, California).

This year marks the 35th anniversary of RenderMan, which has received numerous prestigious awards over the years, with one coming as recent as December 2023. Some of the awards include:

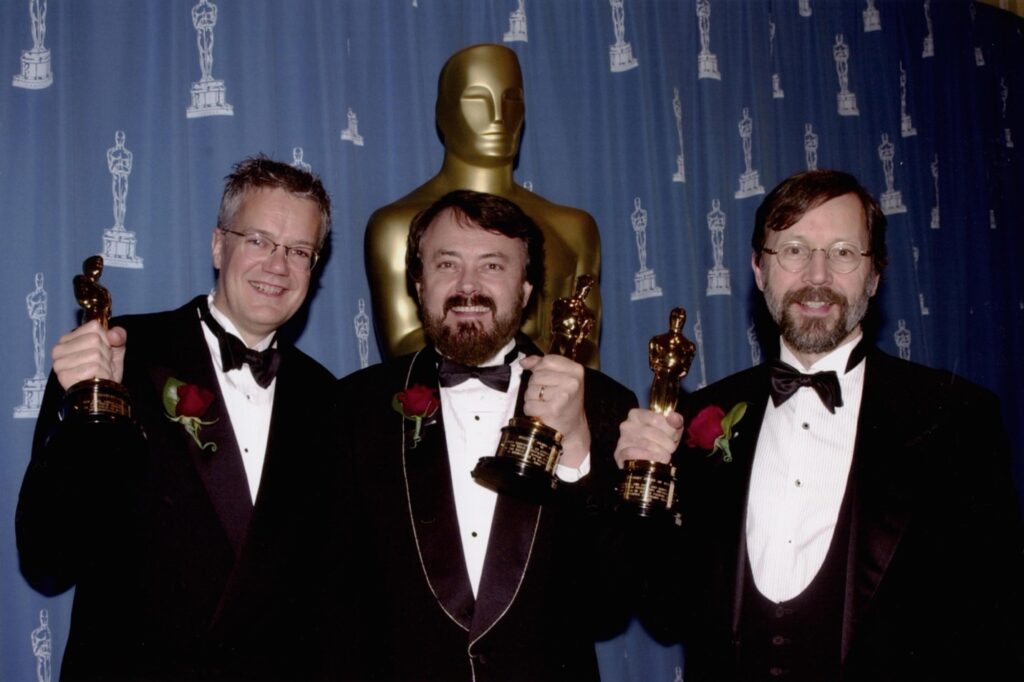

- 1993—Scientific & Engineering Achievement Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for RenderMan’s contribution to the motion-picture industry (Loren Carpenter, Rob Cook, Ed Catmull, Thomas Porter, Pat Hanrahan, Tony Apodaca, and Darwyn Peachey).

- 2001—Academy Award of Merit “Oscar” for significant advancements to the field of motion-picture rendering as exemplified in Pixar’s RenderMan. This was the first Oscar awarded to the developers of a software package for its outstanding contributions to the field (Ed Catmull, Loren Carpenter, and Rob Cook).

- 2009—The Coons Award (Siggraph 2009) presented to Rob Cook (VP of advanced technology, Pixar Animation Studios) for his foundational contributions to physically based reflectance models and distribution ray tracing, and his enduring work on behalf of the Siggraph community.

- 2009—The Gordon E. Sawyer Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences honoring Ed Catmull for a lifetime of technical contributions and leadership in the field of computer graphics for the motion-picture industry, including his work with Pixar’s RenderMan.

- 2010—Scientific & Engineering Award for the development of point-based rendering for indirect illumination and ambient occlusion, and featured in Pixar’s RenderMan. Much faster than previous ray-traced methods, this computer graphics technique has enabled color-bleeding effects and realistic shadows for complex scenes in motion pictures (Per Christensen, Christophe Hery, and Michael Bunnell).

- 2011—Scientific & Engineering Award for work on Pixar’s Alfred render queue management system (David Laur). Also, a total of six developers were honored for their work on various queueing systems, which have allowed studios to process the large amounts of data required for 3D animation and visual effects.

- 2023—IEEE Milestone Award for pioneering work in computer graphics, marking a momentous milestone for Pixar’s flagship RenderMan renderer.

While Sisson recognizes that Pixar’s RenderMan group is a business, he maintains that its biggest focal point is innovation, “and that’s where we want to stay.” RenderMan is recognized as the gold standard in rendering, and he attributes that to the fact that the group is allowed to take risks that others with more aggressive financial goals aren’t able to.

“We look at things from a pure artist’s lens, and I think that is important; we don’t have money goggles on,” Sisson says.

Recently, Pixar held its 10th RenderMan art challenge, giving users a chance to work with a production-quality Pixar scene and render it in the cloud via Microsoft Azure on the AMD Creator Cloud. The theme of this challenge was “Lost Things,” whereby members of the RenderMan community (commercial and non-commercial users) were prompted to showcase their shading, lighting, rendering, and compositing skills. In that and previous challenges, artists had the rare opportunity to receive critiques from the RenderMan team, giving them a chance to learn and develop their skills (they are encouraged to post work in progress and ask technical questions. The challenges are intended to let participants try new techniques. Winners are judged on narrative (story and composition) and technical (texturing/shading and lighting/rendering), with the winners receiving valuable prizes from the sponsors. The next challenge will be announced at Siggraph 2024 in Denver this summer.

As Pixar stated in a recent online post after receiving its IEEE Milestone Award: “The tech developed here at Pixar was essential to bringing lifelike lighting, smooth animation, and so many beloved characters to life, forever changing the landscape of animation and film.”