Proprietary systems play a critical role in advancing technology. Companies invest in developing solutions to address problems that existing technologies can’t solve. If successful, they profit from their investment. These proprietary systems have driven industry progress, developed through significant financial and human capital investment. Successful proprietary systems often become open standards, involving committees and creating specifications, which can slow development. However, competitive pressures drive faster product development by individual companies, bringing needed technology to market more swiftly. If proprietary solutions don’t become cheaper over time, competitors and customers push for open, free versions.

Proprietary systems propel the industry. Companies develop a solution to solve a problem that can’t be solved with current technology. They make the investment, apply their engineers to it, and if it works, reap a return on that investment. They take the risk, and they get the reward.

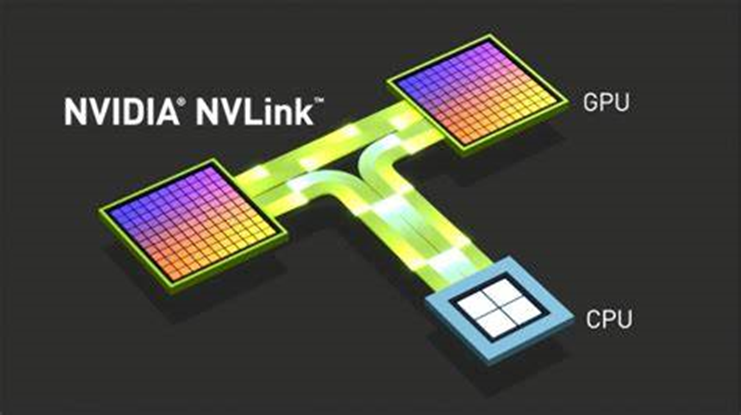

Windows is a proprietary system, x86 was for a while, the GL API was, and DirectX still is, CMOS memory was, and so was Ethernet. Nvidia’s CUDA and NVLink are proprietary systems. All of those systems have moved the industry forward, and all of them were developed by a company with its financial and human capital.

At Computex, AMD’s CEO Lisa Su and Intel’s CEO Pat Gelsinger spoke at their keynotes to advocate for the upcoming Ultra Accelerator standard UALink. Gelsinger said, “Customers don’t want proprietary islands of infrastructure in their data centers.” Evidently, he forgot about Xeon processors.

But something about NVLink has gotten up the noses of the data center operators, and maybe it was the exclusivity of NVLink to Nvidia GPUs. As a result, AMD, Broadcom, Cisco, Google, HPE, Intel, Meta, and Microsoft have come out in support of UALink, which offers an alternative to NVLink for other GPUs like AMD’s and Intel’s. AMD and Intel are about to have their democratization of the data center philosophies tested as Arm-based servers enter the market.

If a proprietary system is introduced and successful, it is very often opened up and given to the industry. That usually slows the upgrade or expansion process as more cooks make the soup. Committees are formed, specifications are created, and sometimes testing and certification policies and procedures are developed, all by committee—i.e., it is time-consuming.

However, industry demands and competitive pressures are high, so a less bureaucratically bound product development process that a single company (or sometimes two) can launch brings the newer, needed technology to the market faster. No one complains when that happens, but if the proprietary solution doesn’t drop in price over time, competitors criticize, and customers complain and the push for an open, free version emerges.

A fast technological company will always outpace a committee. However, a committee can bring more resources to the problem and a more expansive experience history, and the committee members work for free. We’ve seen this play out in Khronos, the PCIe SIG, and Vesa. It’s reasonable to expect the UALink org to have similar success. But it is also unlikely we’ll see anything tangible from the organization in less than two years. And as the UALink does its work, it’s highly probable we’ll see other proprietary solutions emerge that may be woven into the UALink. Some proprietary systems like Windows and CUDA never get opened up; typically hardware systems do more often. UALink will be a hardware system with a complex software stack, and that’s where the development time will get eaten up. But if it follows the path of PCIe Bluetooth and USB, UALink will fill a need and become a critical infrastructure component.